Table of Contents

James Webb Space Telescope

James Webb Space Telescope has solved another cosmic mystery.Astronomers can see a type of light emitted billions of years ago from some of the earliest galaxies, yet many scientists don’t think this light should be visible. That’s because, at a crucial time in the universe’s history — a time called “reionization” when the first stars began to glow — space was absolutely packed with gas spawned by the Big Bang (the pivotal explosion that created our universe).

New Webb Research

Such thick gas should shroud this light from the first stars and galaxies. But it doesn’t. We can see light emitted from early hydrogen atoms (the smallest atom, and one of the first elements ever formed).

“One of the most puzzling issues that previous observations presented was the detection of light from hydrogen atoms in the very early Universe, which should have been entirely blocked by the pristine neutral gas that was formed after the Big-Bang,” Callum Witten, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge who led the new James Webb space research on this mystery, said in a statement. “Many hypotheses have previously been suggested to explain the great escape of this ‘inexplicable’ emission.”

But the James Webb space telescope, built with a huge mirror to detect extremely faint light and resolve extremely distant objects, has provided a compelling answer.

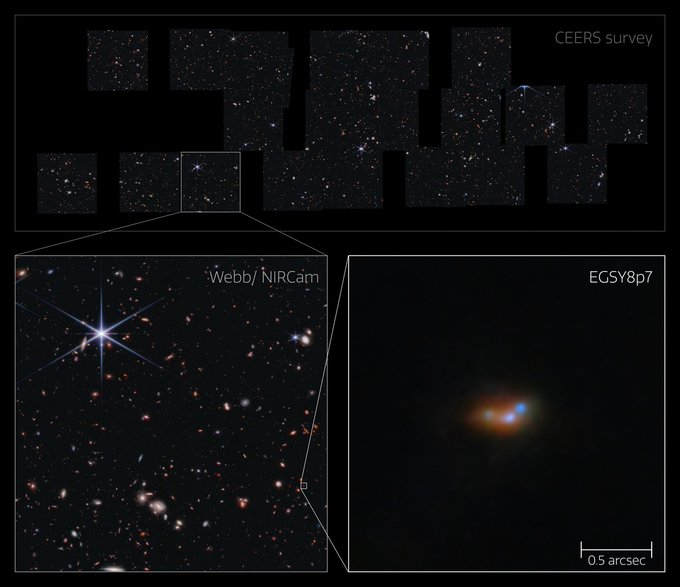

It turns out the “inexplicable” light previously observed coming from a particular ancient galaxy isn’t just coming from a single galaxy. Webb found that these emissions are actually coming from groups of galaxies — we just couldn’t see them.

Journal Nature Astronomy

These early galaxies were colliding and merging with one another (galaxies often collide), ultimately creating an extremely active cosmic environment. In the new research, published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Astronomy, researchers found that this intensive activity — galactic collisions stoking the vigorous creation of new stars — generated strong light emissions and also cleared the way for the light to escape into space.

The Webb image below shows the distant galaxy EGSY8p, located a whopping 13.2 billion light-years from Earth, surrounded by two other smaller galaxies — something previous observations couldn’t detect.

“Where Hubble was seeing only a large galaxy, Webb sees a cluster of smaller interacting galaxies, and this revelation has had a huge impact on our understanding of the unexpected hydrogen emission from some of the first galaxies,” Sergio Martin-Alvarez, a researcher at Stanford University who worked on the new study, noted in a statement.

The remarkable powers of the Webb telescope

The Webb telescope, a scientific collaboration between NASA, ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency, aims to investigate the furthest regions of space and provide fresh insights into the early cosmos. But it’s also about exploring the interesting worlds within our galaxy and the planets and moons within our solar system.

Astronomers will continue to direct Webb at some of the earliest galaxies that ever formed, with the greater goal of understanding how galaxies, like our own Milky Way, came to be.

Massive mirror

Webb’s light-capturing mirror measures more than 21 feet in diameter. That is more than 2.5 times the size of the mirror on the Hubble Space Telescope. By capturing additional light, Webb is able to view more ancient, far-off things. The telescope is seeing stars and galaxies that created more than 13 billion years ago, only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, as previously said.

“We’re going to see the very first stars and galaxies that ever formed,” Jean Creighton, an astronomer and the director of the Manfred Olson Planetarium at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, told Mashable in 2021.